The concept of the rules about the rules was introduced to me by my mother many years ago. At the time, we were talking about rules of behaviour within the family context. The principle of the rules about the rules, as she explained it to me, was that every articulated set of rules is accompanied and governed by an unspoken set of rules that concern things like why rules are followed, from what authority the rules are derived, and so forth. I didn’t realize then that we were dipping our toes into the shallow end of Wittgenstein. My upbringing was pretty meta at times.

The significance of rules

As soon as you start thinking about rules in this way, the vastness of the universe of rules becomes almost overwhelming. Rules govern our every action. And by our rules, and the rules of others, we are measured and assessed, in terms not only of how good we are at remembering one set of rules or another, but even the nature of our characters – what type of people we are, and how others will relate to us once the pattern of our adherence to rules is ascertained.

Think about it for a minute. A job interview is a determination of what rule sets you’re familiar with, and how good you are at following them. Please provide examples and references. And the interviewing doesn’t end when you get the contract. Even once you’ve set up your desk phone and carefully arranged your pens in that cleverly personalized coffee mug that you don’t really ever want to drink from, people still want to know what rules you follow so they can decide if you’re one of them.

Rules to follow and rules to unlearn

I have found, on a number of occasions, that the start of a new contract is heralded by a brief interrogation about rules. People want to know how I feel about serial commas, or ending sentences with prepositions. My answer these days, which I’ll admit rarely garners me new friends, is that rules are for people who need something to cling to. I’ll use a serial comma if I think it’s appropriate and helpful to the reader. But I’m a professional writer. I work without a net.

Of course there are rules that must be followed; there can be no language without a consensus on what words mean, how they function, and what sort of order we expect them to arrive in. Then there are rules that we are told about language by people who are trying to be helpful. These rules generally come with so many qualifications and exceptions that as rules they are of no practical use at all. The best example of this is ‘i’ before ‘e’ except after ‘c.’ But there are many others like it.

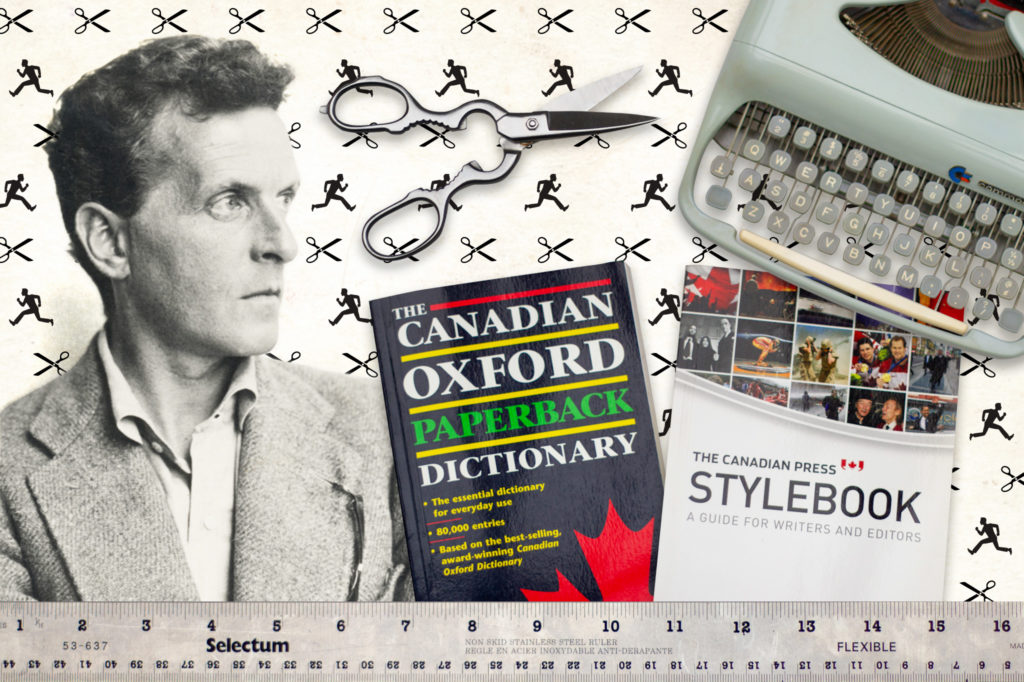

Running with scissors

These rules are taught to us when we are young, usually in a sincere effort to keep us out of trouble. They fall under the generous umbrella of don’t run with scissors. Sure, running with scissors isn’t usually a great idea. But we’re adults now, and we can recognize a scissor emergency when we see one, and if we need to get the scissors from one end of the house to the other in a hurry we can be trusted to do what needs to be done.

You will, however, in your career as a freelance writer, come across people who have taken those childhood rules to heart and carried them well into their adult lives. I was once told by a client, during a presentation, to remove all instances of the word “but” from the copy I had written for his website. He explained to me that “but” is the destroyer, and it negates everything that comes before it. “My sixth grade teacher taught me that,” he declared proudly. I somehow resisted the urge to suggest he look his sixth grade teacher up to ask if she was available to write his website for him.

Deciding what rules to use

Most of your larger clients will have style guides already. If one isn’t provided to you as part of the brief, you should ask for it, to forestall disagreements over the rules before they happen. But I think it’s a good idea to have a sense of your own personal style guide, even if you don’t feel the need to codify it in a formal document (that time isn’t billable).

I try not to be dogmatic about it, but as the great Saul Bass said, “we must have a reason for everything we do.” You may be asked, at any moment, why you wrote something a particular way, and if you have a rationale at the ready it means you’ve already put some thought into the problem. I treasure the CP Stylebook, the Canadian Oxford, sentence case headlines, and ISO 8601 date formatting, for example. I will occasionally take great pleasure in writing a sentence that others will inevitably say is too long. And I will fearlessly start a paragraph with a conjunction if I feel the situation calls for it.

Make your own rules

This idea of creating your own style guide isn’t about filling your life with more rules of course. It’s more about identifying which rules you already follow, so that you can readily defend your own personal style when asked. And you will be asked. Your own rules are there to comfort you, not restrict you. And just to keep it all in perspective, English itself isn’t great at following its own rules. I don’t recommend choosing grammar as a hill to die on. It will be an ugly death.

In short, don’t let anyone else’s rules stand in the way of your writing being the best it can be. Not even mine. You’re the writer. You’re in charge of your copy. At least until the client gets hold of it.

This article also appeared on Medium.