I really have to work on my rhetorical style. And by that I mean to say that I don’t think it’s the rhetoric that’s the problem so much as the delivery. I make what I think is – what I know to be a perfect conversation-ender and then turn as if to walk away, and at that instant, someone says “Yeah, it’s like when…” Some of them know what they’ve done as soon as they do it. “I have nothing to add,” a colleague once stammered. “And now you’ve added it,” I told him.

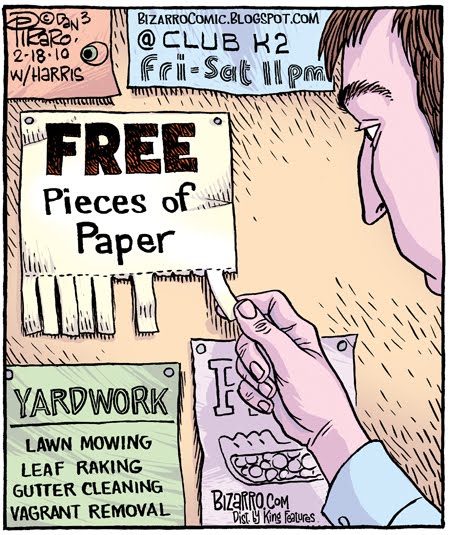

And so it was when I sent out the above cartoon to some marketing colleagues. What I expected were replies along the lines of “LOL” or perhaps knowing nods in the company kitchen, accompanying co-workers saying, “Got that thing, it was effing righteous.” But that’s not what I got. I got, “You should write a blog post about that.”

Now I’m in the awkward position of trying to elucidate what we could have all pretended was some wry, sage, unspoken statement about our jobs, and the state of marketing in general, and left it at that. But we didn’t pretend, or leave it at that, and so this blog post is going to be like The Gospel According to Peanuts, only about a million times more soulless.

Just as a quick recap, I work in marketing. I work for an advertising company. So I can truthfully say, when asked my occupation, that I am a writer who works for an advertising company. But the question that always follows that is, “Have I seen any of your work?” And my truthful answer is always, “No, not that kind of advertising. Not the cool advertising. I write mostly digital and direct. What you unwashed masses would refer to as banner ads and junk mail.” It would be equally truthful for me to continue to explain that there is more, oh, so much more to it than that, but just because it’s the truth doesn’t mean it’s worth my time to explain, or yours to listen. Suffice it to say, this ain’t Mad Men.

Likewise, the idea that the client insists that we make the logo bigger is a trope, but with the kind of blue-chip clients we deal with it’s not even so true anymore. They don’t have to tell us how big to make the logo; they have a cirlux-bound book of brand standards that we swore on as if it were a floppy bible, on pain of a thousand mind-numbing emails from a cadre of humourless corporate lawyers, that tells us on their behalf. And if you didn’t spot the redundancy in the last sentence, it was the word humourless.

What we do get asked to do, however, is make the call to action bigger (like so many things in our business, the part of the ad that tells you what to do has a super-secret marketing name and an acronym to go with it). The call to action, or CTA, is the “act now” bit at the end; the URL; the 800 number; the part that tells you what to do if you like the thing that the ad is telling you about. The CTA has to pop. It has to be in a coloured box. It should, perhaps, be a “hot” colour like red or yellow. A former president at one agency I have worked at called, quite straight-facedly, for a design standard in which the CTA was “as big as the headline.”

Well I used to be an art director, and I still have some vestigial knowledge of what kinds of problems these suggestions can cause from a perspective of visual aesthetics. And what you can’t really tell people about aesthetics in marketing and advertising if they don’t already believe it is that the way your stuff looks, in particular how good it looks, how much respect it shows for the visual cortex of your audience, speaks to the character of your brand as clearly as your headlines – which is why a former creative director of mine suggested, in typically diplomatic and understated terms, that we attempt to “err on the side of good taste.”

And what I know as a writer (a senior writer, if you please), is that no one is going to act now, or act at any time, if that action isn’t going to make them better off, in their own estimation, than they would be if they did nothing. Which means we have to give some weight and thought to what the hell is so cool about what we’re trying to sell them. This seems obvious to me, and to many people I talk to – but surprisingly it’s not obvious to absolutely everyone. I don’t fault my clients for loving their products. Their products are as much their children as my first draft copy decks are mine. But unless you’re Apple (and maybe we’ll have a chat about blind Apple adoration sometime in the future) you are on thin ice if you just assume that a big old hero shot of your product and a bone-dry list of techs and specs is enough to compel them to jam a crowbar into their wallets and buy one from you.

Look at it this way. All offers are essentially discounts. Order by x date and save y. Or maybe we’ll send you some kind of tchotchke or throw in some service that we’re going to try to convince you that you wanted anyway, so by giving it to you for free we’re saving you money; same difference. But a discount on something your potential customer is not sure he or she wants – about which the benefit has not been communicated to their satisfaction – is hardly a bargain. You might as well be giving away free pieces of paper. But if you can manage to convince them that your product is worth owning, and will benefit them in some way, they might end up actually wanting to read the CTA. And if the reader is actively seeking it out, maybe it doesn’t have to be the same size as the headline, or in a neon colour, or in a starburst. Maybe you can shrink it down to a more reasonable size.

Like, say, the logo.

As one of the people who put you in this awkward position, all I can say is, I’m glad I did. As a consumer, why should I care about what you’re selling? It’s not the product that sells itself, it’s the story we tell people about the product that sells it. That’s as true for the Shamwow as it is for a BMW.